“Raised on porridge and song in a family of eccentric musicians in Reading,” Kate Fletcher first came to our attention as the singer and main songwriter of Epona - a short-lived but influential English folk-rock group whose alumni include her brothers Colin and Jon - latterly of Telling The Bees and Magpie Lane, respectively, and Nancy Kerr. They released a fine album entitled Shine Again in 1997, after which Kate retreated from recording for ten years, returning with her solo CD Fruit (recorded in a caravan by Leveret’s Rob Harbron) in 2007. Ten years later (she’s nothing if not consistent) Kate’s back with Fishe or Fowle - her first album as as a duo with her husband Corwen Broch, and (astonishingly) his debut recording.

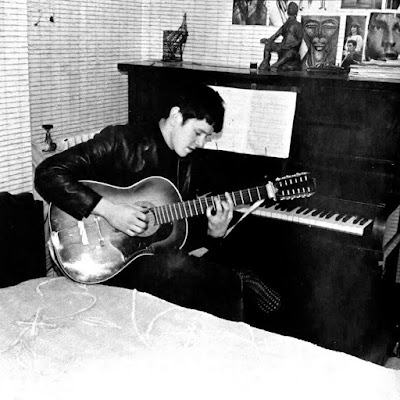

“I always wanted to be a musician” Corwen tells me over the phone from Orkney (where Kate works as a music teacher) “but I didn’t really have any musical background or way into it. When I was 21, I bought a truck and started living on the road. I met a bunch of people at Wayland’s Smithy and from them I picked up some drumming and didgeridoo - all the terrible hippie instruments! Then a couple of years later I learned tin whistle and bodhran and joined a band called Senzar Tribal Collective, which was really a rounding-up operation of everyone in Boscombe who was stoned enough to agree to come and play - but not so stoned that they couldn’t come and play! Then I joined a little Irish trad pub band called Celtic Dream - which sounds like a liqueur, and that was a hilarious bunch of people. I was still living on the road and on protest sites in my late twenties when a wealthy Druidess kindly bought me a set of Welsh bagpipes made by John Tose, and that was a turning point.” I first met Kate after being drafted in to deputise for her regular musical partner at a medieval music and storytelling show.”

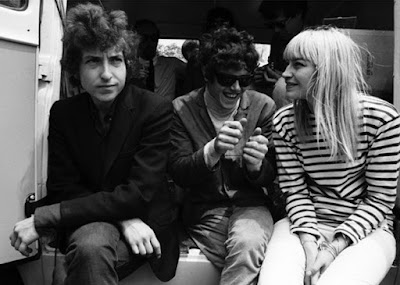

“We became a couple because we had compatible reed instruments,” Corwen deadpans, but, as they soon discovered, their musical compatibility runs deep.

“We’re both real believers in maintaining traditional customs and the purpose of music as something more than just commercial, consumer entertainment,” says Kate. “It has social and ritual functions for dancing, for remembering, for bringing communities together. We’ve amassed a huge collection of CD and DVD resources to explore traditions. When we found out that Folktrax was folding (in September 2007) we bought everything we thought we’d ever need. That’s where the two samples of the old ladies on Fishe & Fowle come from - they’re Peter Kennedy recordings that now belong to Topic. We made a conscious effort to really honour and credit those source singers, because Kennedy didn’t always do that.”

Fish or Fowle is a double CD release, with eleven traditional songs and four originals on disc one, while the second disc is the first recording for 30 years of The Play o' de Lathie Odivere, an Orcadian ballad, sung in five parts. All of the songs are concerned with themes of transformation, as Corwen elaborates.

“There’s a marvellous book called Folklore In The English and Scottish Ballads (Lowry Charles Wimberly) which is full of fantastic stuff about ghosts, the afterlife, fairies, and all the cosmology that you can work out from the ballad tradition. One of the ideas is of a very permeable barrier between human persons and other-than-human persons. In the ballad tradition, people turn into animals, animals turn into people, animals speak… The album explores liminality between human and other-than-human and the desire for transformation and the fear of transformation. People resist hugely the idea that we might be animals , even though we demonstrably are! We can only be animals, plants, fungi or bacteria… Our animal nature and our kinship with the wild is really something to be embraced, and by distancing ourselves from the natural world we really impoverish ourselves.”

That Fish or Fowle is a unique-sounding record is due in no small part to the instruments used in its creation. “Corwen made the first Shetland gue in over a century!” Kate enthuses. “One of his instruments is in the Shetland museum, and he’s lectured in Scandinavia on the British bowed lyre traditions including the Shetland gue and the Welsh crwth. A lot of the instruments on the album we made ourselves, and we were very selective with the sounds that we used. We limited ourselves to producing a sound that’s very ancient, but not necessarily played in an ancient way. We’re not trying to recreate something - the minute you do that, you’ve made a museum piece and killed it. Almost every song that we sing has had changes made by us. They’re not fossilised pieces - even the oldest, most traditional songs are very personal to us in some way.”

katecorwen.bandcamp.com