Originally published in fRoots magazine Nos.385/386, August/September 2015

Catching The Wind

This year marks Donovan’s fiftieth anniversary as a recording artist; a half-century in which he’s released hit records and been inducted into the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall Of Fame. In recent years, his associations with famous friends like Bob Dylan, Graham Nash, Jimmy Page, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles have frequently seen his achievements positioned as a sidebar to the stories of others, and the oft-repeated anecdotes dismissed as mere hubris by those too young to remember his heyday.

Catching The Wind

Back in 1965 however, Donovan was what used to be called a folksinger, albeit one with a singularly unusual career path. Still a teenager when catapulted to stardom, he was awarded an Ivor Novello Award for his debut single (the timelessly lovely Catch The Wind.) While his contemporaries honed their craft in the safe havens of folk clubs, Donovan - subjected to the full glare of the public spotlight, was urging the readers of teen magazines to listen to Bob Davenport & The Rakes. Time to ask some different questions…

|

| Catch The Wind |

“Hell-oo!” says the unmistakable voice on the telephone, from his home in Ireland. “So… you want me to talk about folk music?” Oh ‘deed I do…

“For the first ten years of my life I lived in Glasgow, where I listened to folk songs at family parties. Each relative would sing a song - aunts, uncles, family friends. A chair would be put in the middle of an empty room at these parties and a slightly tipsy relative or friend would be pushed onto it and asked to sing their song. Many of the songs, though I didn’t know it at the time, were folk songs from Ireland and Scotland - we’re talking about The Wild Colonial Boy, Over The Sea To Skye, Mairi’s Wedding, and they were always sung unaccompanied.”

“Also, my father, Donald, used to read me poetry by rambling poets like Robert Service and WH Davies - who was an English guy who travelled into America and rode the trains during the depression. When I got my first taste of recorded American folk music - Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Jack Elliott and all that good stuff, I found I was listening to things that I’d already heard my father read as poems.”

|

| Glasgow in the 1950s |

After the family moved to Hertfordshire, young Don quickly became enamoured with the new rock ’n’ roll sounds.

“The Everly Brothers and Buddy Holly appealed to me tremendously. Of course, I didn’t know then that the Everly Brothers had an Irish granny too! At fifteen or sixteen I left school and managed to get in to a further education college, and that was the start of becoming completely plugged-in to what one would call the ‘bohemian scene,’ of St Albans. Hatfield and Welwyn Garden City. That’s when I became aware of the folk scene that was going on at the time. It was jazz first - the New Orleans revival played by Acker Bilk, Ken Colyer and Chris Barber.”

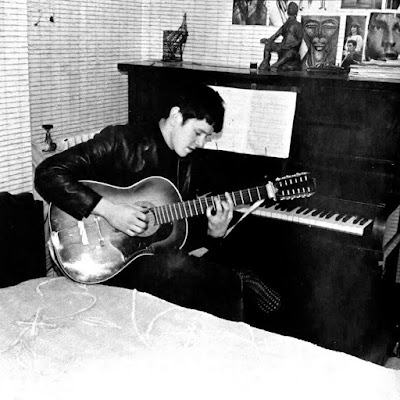

“Somehow, the folk music was starting to influence me and I used to go to the folk club in St Albans, where the visiting singers like Alex Campbell and Jack Elliott played. The guitar was my second instrument, as I played drums first - the jazz groove was what blew me away. My pal Mick Sharman played guitar and he showed me some chords and taught me to play a couple of Hank Williams songs, and I was hooked! Eventually I was able to borrow a Zenith f-hole guitar from Mick’s girlfriend which was much better than the guitar I was learning on - a Spanish guitar, but with steel strings. That was a bugger to tune - impossible!”

“I’d started learning a few songs from Joan Baez and Woody Guthrie records, but it wasn’t until I got hold of that Zenith that I started seriously wanting to learn. I first heard Woody Guthrie’s songs from Jack Elliott, and he fascinated me. I saw that he was playing with Derroll Adams and one thing led to another as time went on, and Derroll Adams became a mentor for me. I followed Derroll around - and this is after I’d already made my earliest records. Colours is really influenced by Derroll. Even the way he touched the strings of his banjo fascinated me. He was a student of Zen Buddhism, and he played that banjo like a Japanese koto, or something. So I’d sit with him for hours, listening and looking at what he was doing - he taught me a lot.”

|

| Donovan and Derroll Adams |

“From hearing songs in the folk club, I used to go to the record shop in St Albans and listen to loads of albums, even though I couldn’t afford to buy them - traditional British folk music on the Topic label and stuff like that. Then, when I saw Martin Carthy on stage, that was a great breakthrough, I mean Martin had it down! He was already playing the guitar in a very different way, and performing all those British ballads collected by Francis Child. I knew that Joan Baez had recorded some of these Child ballads, but seeing Martin really made me aware of them.”

For all Donovan’s admiration for Martin Carthy, it was another British singer and guitar player who would make the greatest impression on him.

“Bert Jansch became my teacher in 1965. Bert played British folk tunes too, but slapped and attacked the strings like a blues player - just amazing playing. He’d do these incredible descending runs behind the tune - something he probably learned from Davy Graham, but Bert was my man, I loved what he was doing. Bert was really very good to me - the magnanimity of the artist came out of him. He slowed it all down for me, and that was important. One night in Bert’s kitchen, he showed me the D9 chord, from which I started writing Season Of The Witch, with the descending chord progression from Angi. John Renbourn says I played Season of The Witch in Bert’s kitchen for seven hours straight, so that’s the kind of kitchen Bert had!”

|

| Bert Jansch and John Renbourn |

1965 also saw Donovan heading to America, where he performed at the Newport Folk Festival and appeared on Pete Seeger’s Rainbow Quest.

“It all happened really fast! Derroll introduced me to Buffy Sainte Marie, as I’d already learned two or three of her songs, and listened to all of her songs. Then Buffy introduced me to Joan Baez, who called up Pete Seeger and said: ‘Donovan’s got to be part of the Newport Folk Festival’ - and that’s what she’d done for Bob Dylan two years earlier, of course. Joan was tremendously helpful to me. So there I was, on the plane to go to to the Newport Folk Festival and also straight to Rainbow Quest with Rev. Gary Davis!

If you were a guitar picker then, there were two essential songs that you had to learn. One of them was Angi by Davy Graham and the other one was Cocaine Blues by Rev. Gary Davis. My early repertoire is drawn very much from folk tradition - Ballad Of Geraldine is based on an old folk song melody, London Town is a Tim Hardin version of Green, Rocky Road. All that hammering-on and pulling-off on Summer Day Reflection Song comes from listening to the Arabic music that Davy Graham and John Renbourn loved, the oud music. There was a lot of that in London - this is before even the sitar became fashionable.”

If you were a guitar picker then, there were two essential songs that you had to learn. One of them was Angi by Davy Graham and the other one was Cocaine Blues by Rev. Gary Davis. My early repertoire is drawn very much from folk tradition - Ballad Of Geraldine is based on an old folk song melody, London Town is a Tim Hardin version of Green, Rocky Road. All that hammering-on and pulling-off on Summer Day Reflection Song comes from listening to the Arabic music that Davy Graham and John Renbourn loved, the oud music. There was a lot of that in London - this is before even the sitar became fashionable.”

|

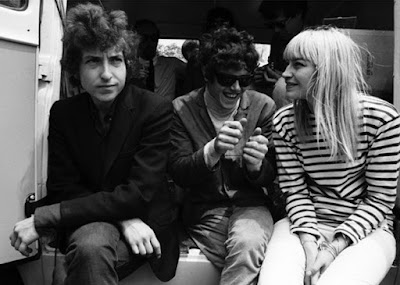

| Newport Folk Festival, 1965. Bob Dylan, Donovan, Mary Travers |

Donovan spends about six months of the year in Ireland, and loves to hear the traditional music.

“When I first came here in 1970 I was plugged-in immediately to what was going on. What was different to the British folk scene was that the traditional music in Ireland wasn’t really recorded until Claddagh Records was created by Garech Browne. He was an aristocrat with a castle and a coach and four horses that he would ride around in with all the Dublin poets in the late 1950s!

|

| Garech Browne with Paddy Moloney of The Chieftains and Rita O'Reilly |

“Anyway, a photographer called Tom Collins told me there were some guys playing in Newbridge he wanted me to hear, and it was Planxty - Liam O’Flynn, Andy Irvine, Donal Lunny and Christy Moore. They were playing in the church hall there, and we invited them back and had a party that lasted a week! I told them they were the Beatles of Irish music and took them on the road with me. Through them I met the guys from Sweeney’s Men, who Andy had been with, and started learning from them the facts of how this music was passed on, and that there were pockets across the west coast where these real, traditional fiddlers still played. Then, many years later, I met Seamus Begley and Steve Cooney and the new tradition. First I met Planxty and Maire Brennan of Clannad, then when we came back here in 1989 we ran into the Waterboys and Sharon Shannon and all those guys. That was an amazing scene too. We’d go to pubs with these people and the owner would lock the door and we’d never go home ’til four in the morning! The fiddles and flutes and the bodhrán and the banjo and guitar, and the girls singing… It’s amazing how Ireland preserved it’s traditional music. And we all know that the Irish and the Scots went over to America and invented pop music!”

|

| Planxty |

If the folk boomers of the early 1960s soundtracked the civil rights movement and the opposition to the Vietnam war, what does Donovan see as the role of today’s troubadours?

“The questions still remain about how do you speak out against inequality, against the Earth’s destruction and against the greedy sods who just want to buy up and waste and eat and pollute? How do you do it? The singer-songwriters of the new generation have to use their understanding of these things and sing about them. Billy Bragg is the only one that really stands out, for me. Maybe we can say that the social commentators in music now are the street-level hip-hop artists rapping about the continuing racial inequality and the power of the bosses to keep the poor down.”

|

| Joan Baez and Donovan on CND march, 1965 |

“The roots of all popular music is folk music and these things never change. So, when you say an artist has gone back to the roots, it means they’ve gone down to get at the sustenance. People think that the roots music is just something from the past, but in actual fact it’s what supports all the music being made today. The smart younger ones like Moby and Jack White go back to the roots to be nurtured, to be fed and to be encouraged into creating new music. That’s what I think about roots, anyway.”

No comments:

Post a Comment